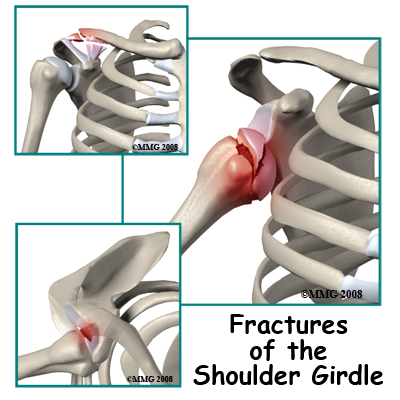

A list of the most common injuries to the shoulder girdle includes:

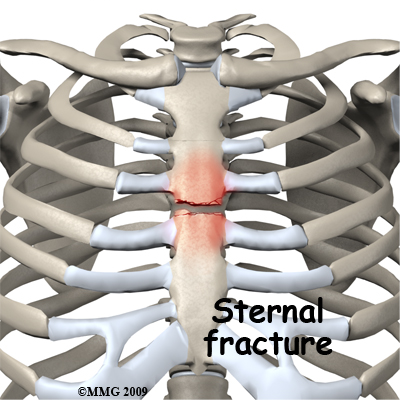

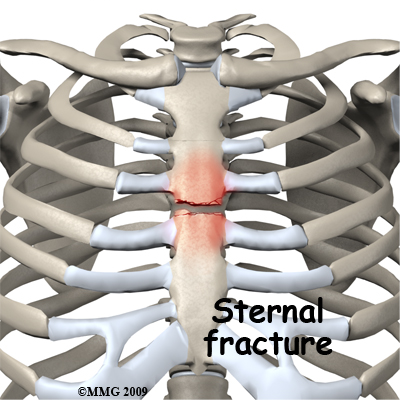

- Fractures of the sternum

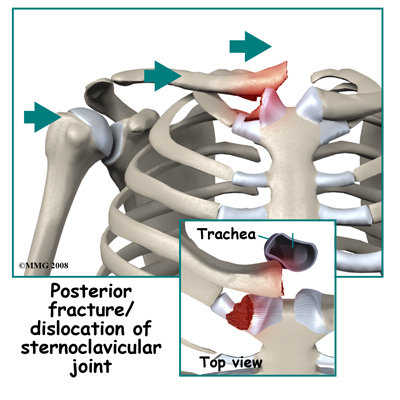

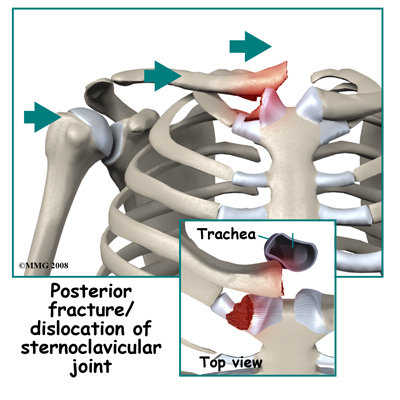

- Dislocations and fracture dislocations of the sternoclavicular joint

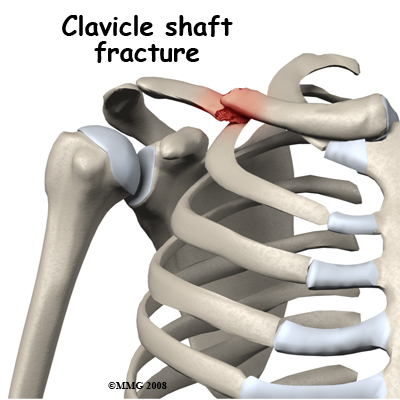

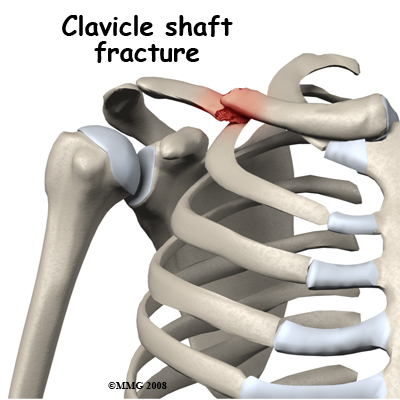

- Fractures of the shaft of the clavicle

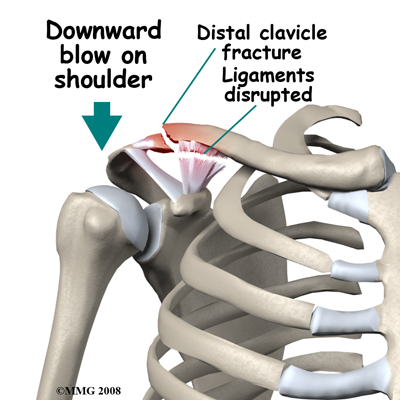

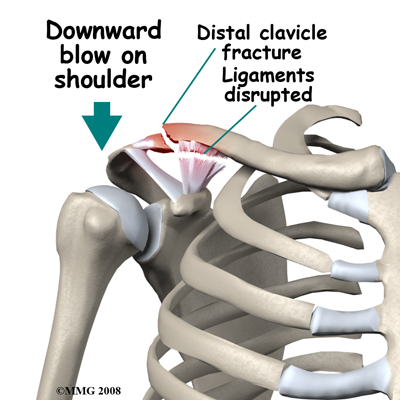

- Fractures of the outer end of the clavicle

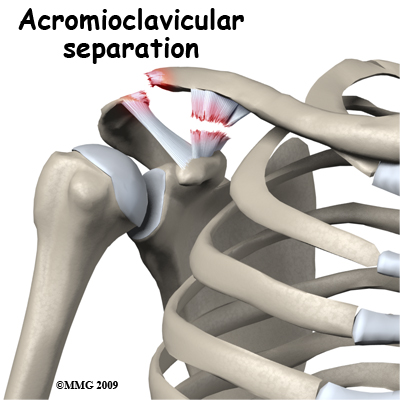

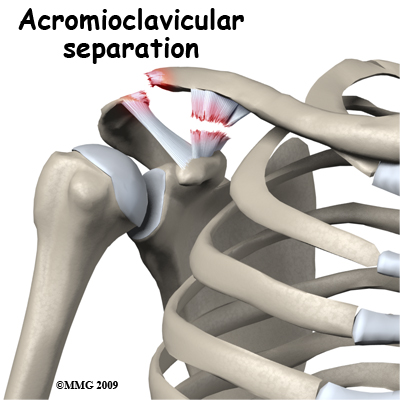

- Acromioclavicular separation

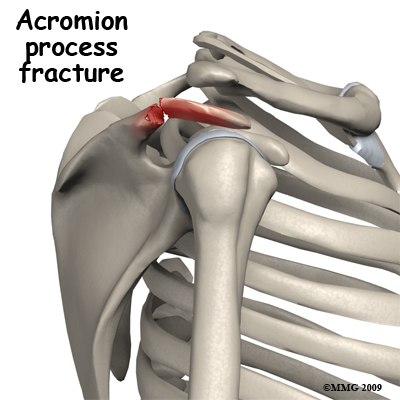

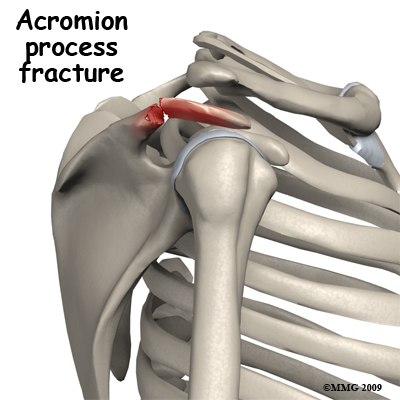

- Fractures of the acromion process

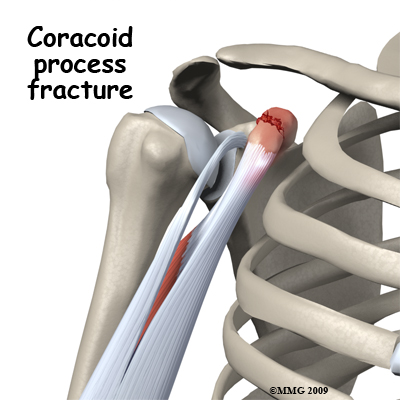

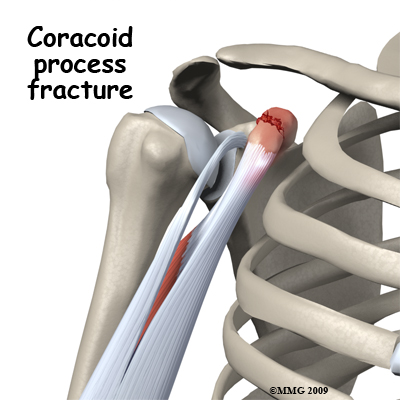

- Fractures of the coracoid process

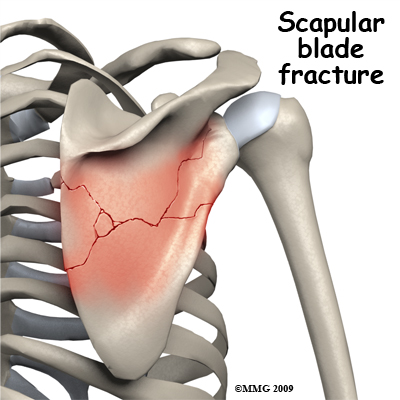

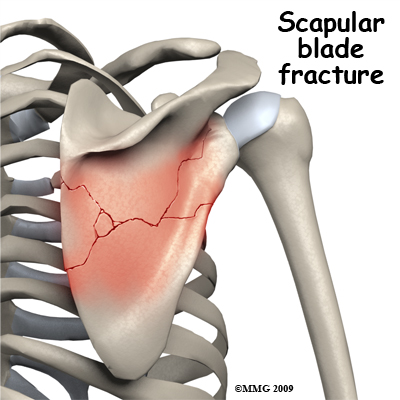

- Fractures of the blade of the scapula

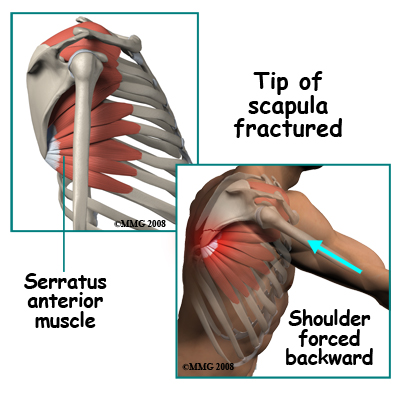

- Fracture of the tip of the scapula

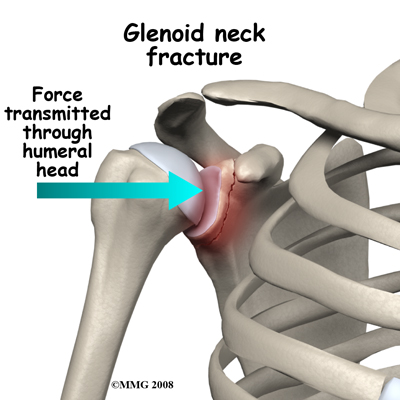

- Fractures of the neck of the glenoid

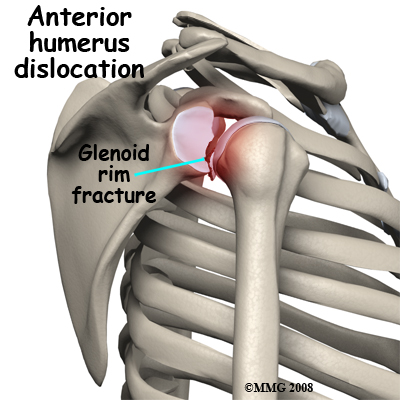

- Fractures of the glenoid

- Glenohumeral dislocation

- Fracture dislocation of the glenohumeral joint

- Fracture of the greater tuberosity

- Head-splitting fracture of the humeral head

- Fracture of the neck of the humerus

Fractures of the sternum are usually caused by impact against the front of the chest such as that caused by the steering wheel in a motor vehicle accident. Even if they are quite displaced these fractures are likely to heal without causing a problem. The impact is in a dangerous area, however, and a sternal fracture may be an indication that vital structures in the chest may also be damaged.

Dislocations and fracture-dislocations of the sternoclavicular joint may be caused by an impact on the region of the joint. Lateral compression on the outside of the shoulder may also be transmitted inward to the joint and force the clavicle to dislocate either in front or behind the sternum. A fragment of the clavicle or the sternum may be broken off as the dislocation occurs. Dislocation behind the sternum may cause serious problems with pressure on vital structures such as the windpipe or the large blood vessels close to the heart. Patients with this injury may need to be transferred to a tertiary center for treatment. The injury is rare and may be quite unstable. The region is more familiar to chest surgeons than most orthopaedic surgeons and it is advisable to have back up from a team capable of dealing with the possibility of damage to large vessels.

A fracture of the shaft of the clavicle is a common injury and is often caused by a direct impact on the mid-portion of the clavicle. A bending force can also cause it where the force that pushes the shoulder back results in a mid-shaft fracture of the clavicle with the outer part angled back. This can be an open fracture as the sharp end of the broken bone cuts through the skin. Mid-shaft clavicle fractures can also be the result of a fall on the outstretched hand. The force is transmitted up to the clavicle, as it is the link between the arm and the rest of the skeleton. Fractures of the shaft of the clavicle have a good reputation for healing and are often treated non-operatively.

Fractures of the outer end of the clavicle are nearly always caused by a downward blow on the shoulder. The arm and shoulder blade are forced downwards breaking the collarbone near its joint with the scapula (the AC joint.) This injury is unstable and usually all the ligaments connecting the collarbone to the shoulder blade are disrupted. The weight of the arm continues to pull the fracture ends apart. Mobility at the fracture site makes it unlikely to heal. For this reason this fracture is usually treated by surgery.

Acromioclavicular separation is usually also caused by a downward blow on the shoulder. In this instance some or all of the ligaments tear but the bone is intact. There is often significant deformity at the joint with the clavicle sticking up like a piano key. The outcome of this injury depends on the degree of ligament damage. When some ligaments are intact the joint will regain its stability and function well. A positive outcome may also occur with more complete ligament tears but it is less predictable. Treatment of significant tears is controversial since the outcome from non-operative treatment may be quite satisfactory whereas earlier methods of surgical treatment had a high incidence of complications. With modern methods of fixation surgical treatment has become more popular.

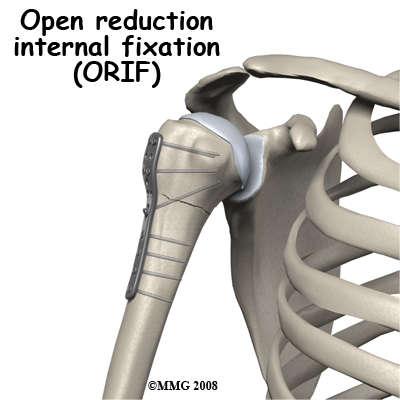

Fractures of the acromion process may be a result of a blow on the tip of the shoulder. Unless the fracture is severely displaced it is unlikely to compromise function of the shoulder joint. Most often this fracture can be treated non-operatively but on occasion it will be treated by surgically opening up the fracture site, replacing the fragment to its original position and then fixing it in place with a screw or other metal implants such as wires, pins, or plates. This procedure is referred to as an open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

Fractures of the coracoid process are nearly always an avulsion fracture. Two muscles that bend the elbow, including the biceps, originate from the coracoid process. If they are contracting to bend the elbow when the load is suddenly increased and the elbow is straightened rapidly, the muscles may pull off their point of attachment. Usually this can be treated non-operatively.

Fractures of the blade of the scapula are usually caused by blows on the back directly to the scapula, often in the context of multiple traumas. The injury itself may be quite spectacular with extensive star shaped fracture patterns, but healing almost always occurs without intervention. A large degree of displacement can be tolerated without loss of function. The main function of the blade of the scapula is as a site of attachment of muscle. On rare occasions the healed scapula is so distorted that the normal gliding motion of the scapula against the ribs is affected and the shoulder blade may catch as it moves over the ribs.

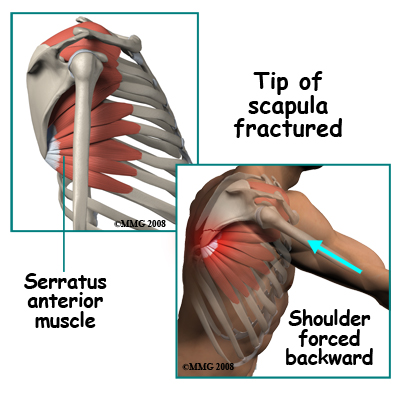

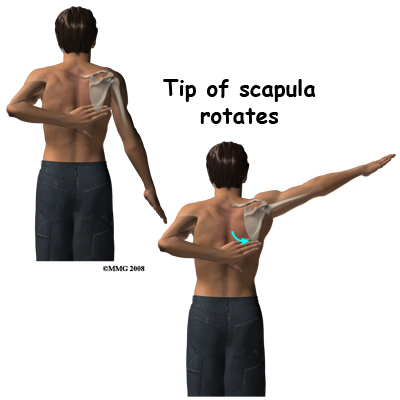

Fracture of the tip of the scapula is usually an avulsion fracture. Powerful muscles attach to the lower tip of the scapula. These muscles act to either rotate or stabilize the scapula against the chest. Since most of the muscles that move the arm attach to the scapula, one important function of the muscles that go between the rib cage and the scapula is to hold the blade still. They tend to "lock" and clamp the scapula to the chest wall. In this situation, if a force on the arm is enough to move the scapula back away from the chest wall, the muscle attachment to the tip is pulled off. Bracing your arm before an impact may result in this injury. Usually it can be treated non-operatively.

Fracture of the tip of the scapula is usually an avulsion fracture. Powerful muscles attach to the lower tip of the scapula. These muscles act to either rotate or stabilize the scapula against the chest. Since most of the muscles that move the arm attach to the scapula, one important function of the muscles that go between the rib cage and the scapula is to hold the blade still. They tend to "lock" and clamp the scapula to the chest wall. In this situation, if a force on the arm is enough to move the scapula back away from the chest wall, the muscle attachment to the tip is pulled off. Bracing your arm before an impact may result in this injury. Usually it can be treated non-operatively.

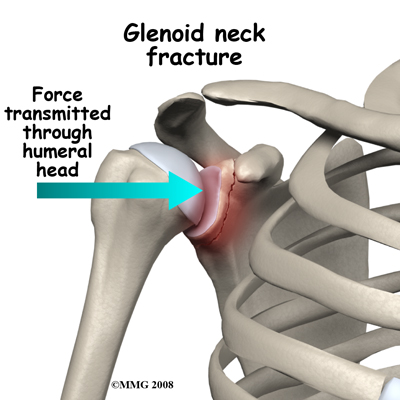

Fractures of the neck of the glenoid occur as a result of lateral compression forces. A blow on the side of the shoulder is transmitted through the head of the humerus to the glenoid. More rarely a fall sideways with the arm out to the side may result in the same type of injury. A very forceful dislocation of the glenohumeral joint might also cause this injury, but fractures of the rim of the glenoid are more common in that situation. Fractures of the neck of the glenoid are also associated with fractures of the blade of the scapula. In most situations the injury can be treated non-operatively.

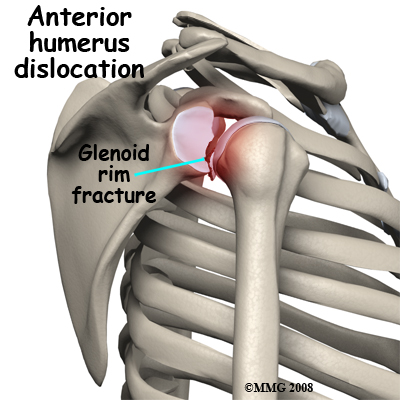

Fractures of the glenoid occur due to the same type of force that fractures the neck of the glenoid. More commonly, a glenoid fracture occurs when the shoulder dislocates and a fragment of the joint goes with it. A fracture involving the glenoid results in an irregular portion of the joint surface. Unless the joint surface is perfectly aligned after the dislocation is back in joint, the fragments are usually treated by surgery (ORIF). Some surgeons may elect to manage this fracture with arthroscopic surgery.

Fractures of the glenoid occur due to the same type of force that fractures the neck of the glenoid. More commonly, a glenoid fracture occurs when the shoulder dislocates and a fragment of the joint goes with it. A fracture involving the glenoid results in an irregular portion of the joint surface. Unless the joint surface is perfectly aligned after the dislocation is back in joint, the fragments are usually treated by surgery (ORIF). Some surgeons may elect to manage this fracture with arthroscopic surgery.

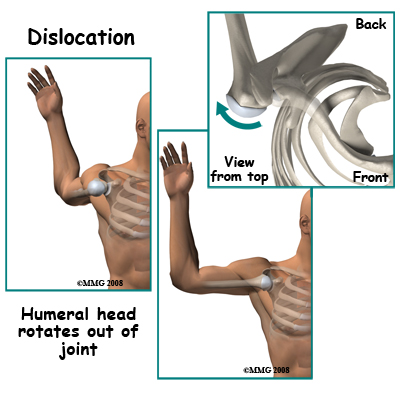

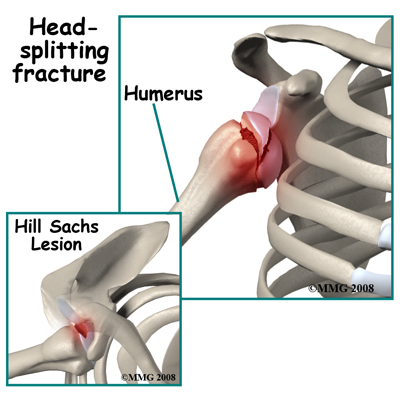

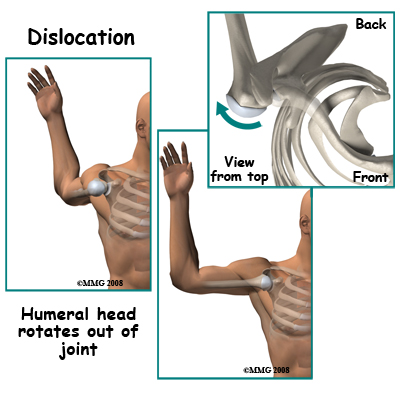

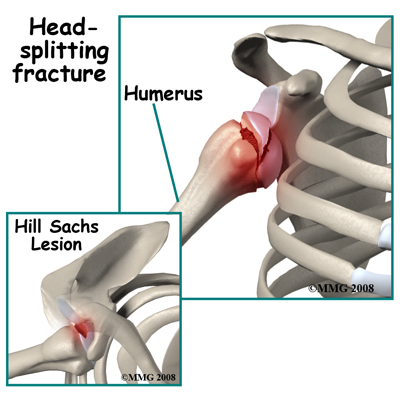

Glenohumeral dislocations result from the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) being moved beyond its limits. The most common position causing this dislocation is excessive abduction and external rotation. Simply put, when the level of the elbow is at or above the shoulder level the hand is forced backwards and the shoulder is therefore pushed forward, out of joint, by a "crank-shaft" action. Dislocation backwards also occurs. The humeral head may be fractured or dented from the impact of it hitting the glenoid rim on dislocation. This is very common after an anterior dislocation. This dent is called a Hill Sachs Lesion. Fortunately it is usually small and rarely needs treatment.

Glenohumeral dislocations result from the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) being moved beyond its limits. The most common position causing this dislocation is excessive abduction and external rotation. Simply put, when the level of the elbow is at or above the shoulder level the hand is forced backwards and the shoulder is therefore pushed forward, out of joint, by a "crank-shaft" action. Dislocation backwards also occurs. The humeral head may be fractured or dented from the impact of it hitting the glenoid rim on dislocation. This is very common after an anterior dislocation. This dent is called a Hill Sachs Lesion. Fortunately it is usually small and rarely needs treatment.

Damage to the axillary nerve occurs quite commonly with anterior dislocation. It is important to look for weakness of the triceps muscle and numbness over the side of the shoulder after a dislocation or suspected dislocation, as these are signs of injury to this nerve.

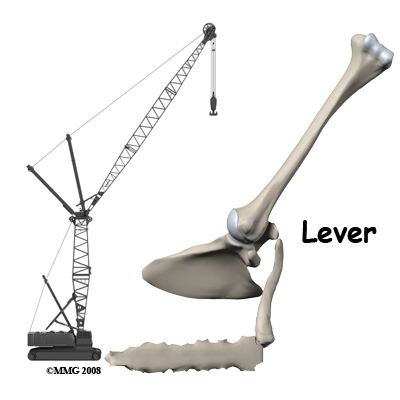

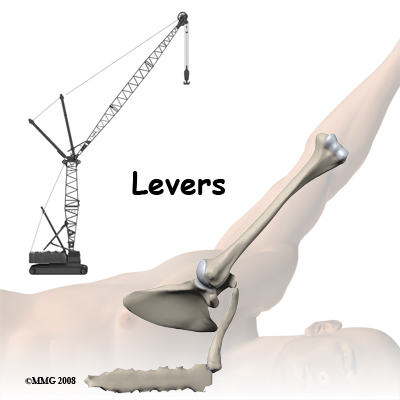

Fracture and dislocation of the glenohumeral joint is rare. It usually results from high velocity trauma with a severe blow to the side of the shoulder. The head of the humerus is driven out of joint and is also broken off the shaft of the humerus. This injury also has a high incidence of injury to nerves. Since the intact humerus is used as a lever arm to reduce most shoulder dislocations a fracture dislocation is difficult to put back in joint. Very frequently it requires an operation to reduce the dislocation and fix the fracture. Even during surgery reducing the humeral head back into joint can be difficult. The joint surface of the humeral head is often damaged in this fracture pattern and it is a challenge to make the shattered bone stable again. Strictly speaking glenoid rim fractures and greater tuberosity fractures may also be fracture dislocations but they have a very different pattern and outcome.

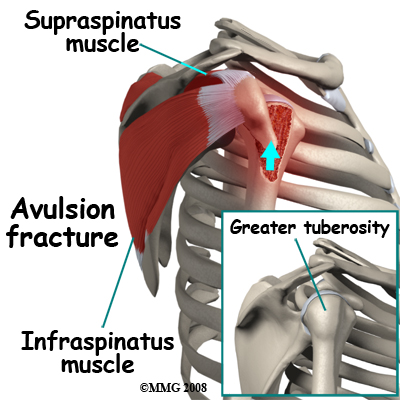

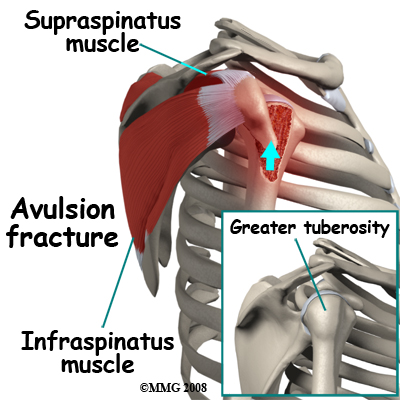

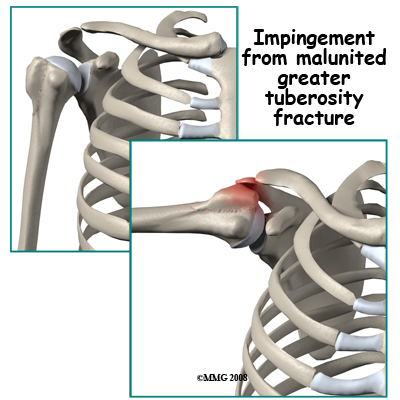

Fracture of the greater tuberosity is an avulsion fracture. By itself it occurs from over-action of two of the rotator cuff muscles - the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. More commonly it happens when there is an anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint. One important function of the rotator cuff muscles is to resist dislocation. If the dislocation happens anyway, despite the pull of these muscles, they may pull off a chunk of bone at their point of attachment, which is the greater tuberosity. After the dislocation has been reduced the shoulder needs to be X-rayed again to determine the position of the greater tuberosity fragment. If it is still significantly displaced it will interfere with abduction and rotation of the glenohumeral joint. In these cases it should be surgically replaced in its position and fixed (ORIF).

Head-splitting fractures of the humeral head only occur when the glenohumeral joint is dislocated. In a violent dislocation the head of the humerus may be driven against the edge of the glenoid splitting a portion of the head off. This injury creates two serious problems. The split fragment has lost its blood supply and the fracture has damaged the joint surface of the head of the humerus. After the dislocation is reduced, it is unusual for the floating fragment to stay in the correct position. Usually this injury must be treated by surgery either to remove the loose piece or to fix it back in position.

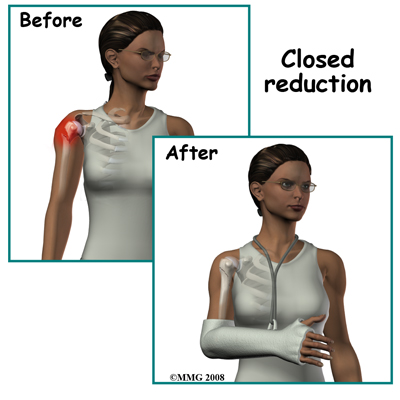

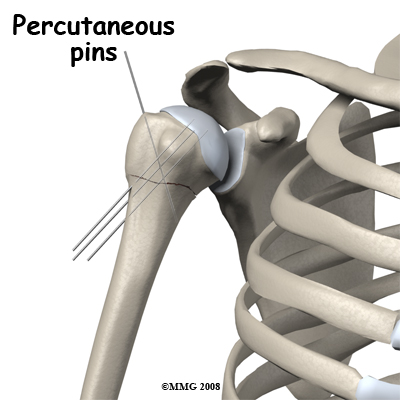

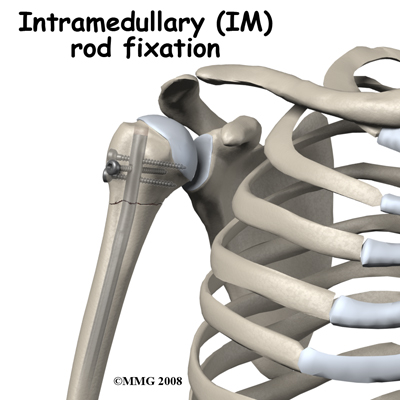

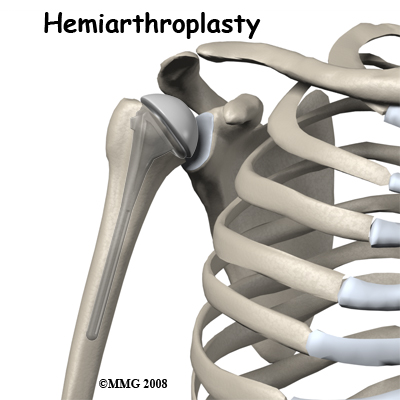

Fracture of the neck of the humerus is one of the most common fractures of the shoulder girdle. It usually occurs as a result of a fall on the outstretched hand with the force being transmitted up to the shoulder. It is a common fragility fracture in the elderly occurring in combination with osteoporosis. The injury can also occur in younger people as a result of more severe forces such as motor vehicle accidents, falls from a height, and collisions in sports. The pattern of fracture in the region of the neck of the humerus can be quite variable. The simplest pattern is a transverse fracture through the neck region. More complex fractures involve other portions of the proximal humerus as well as the transverse fracture. If both the greater and lesser tuberosities are broken off, the blood supply to the head of the humerus is threatened. Due to a range in severity, there are a number of potential ways to treat a fracture of the neck of the humerus ranging from symptomatic treatment only through closed reduction, closed reduction with pin fixation through the skin, ORIF, and in selected cases, a shoulder replacement.

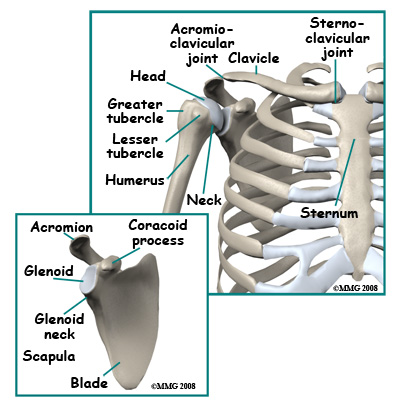

The bones of the shoulder region are the sternum (breastbone), the clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (arm bone). The joint between the sternum and the clavicle is called the sternoclavicular joint. Movement at this joint allows you to shrug your shoulder, pull the shoulder back, or bring it forward.

The bones of the shoulder region are the sternum (breastbone), the clavicle (collarbone), the scapula (shoulder blade), and the humerus (arm bone). The joint between the sternum and the clavicle is called the sternoclavicular joint. Movement at this joint allows you to shrug your shoulder, pull the shoulder back, or bring it forward.

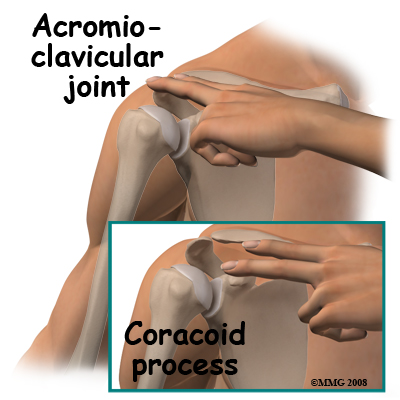

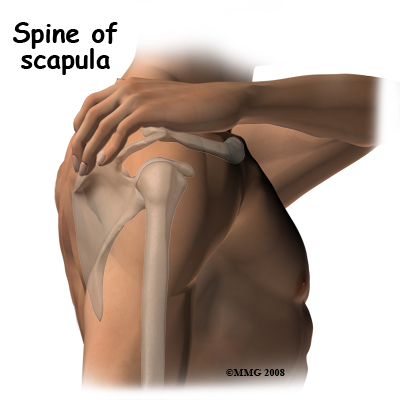

The other parts of the shoulder blade that can easily be felt are the coracoid process, the spine of the scapula, and the tip or distal pole of the shoulder blade. The blade itself is mostly covered with muscle.

The other parts of the shoulder blade that can easily be felt are the coracoid process, the spine of the scapula, and the tip or distal pole of the shoulder blade. The blade itself is mostly covered with muscle.  The coracoid process is a site of origin of muscles and ligaments. If you lay your opposite hand's index finger along the collarbone and press with the middle finger you will feel a hard lump of bone which does not move when you rotate the shoulder. This is the coracoid process; if you bend the elbow you can feel the flexor muscles that attach to the coracoid contracting. These muscles can overact and contract hard enough to pull a piece of bone off of the coracoid process. When the attaching muscle pulls off a piece of the attachment of the bone, it is called an avulsion fracture.

The coracoid process is a site of origin of muscles and ligaments. If you lay your opposite hand's index finger along the collarbone and press with the middle finger you will feel a hard lump of bone which does not move when you rotate the shoulder. This is the coracoid process; if you bend the elbow you can feel the flexor muscles that attach to the coracoid contracting. These muscles can overact and contract hard enough to pull a piece of bone off of the coracoid process. When the attaching muscle pulls off a piece of the attachment of the bone, it is called an avulsion fracture. The tip of the scapula can be felt if you put your other hand behind your back and reach up towards the shoulder. Normally you can just touch the lower tip of the opposite shoulder blade. If you now swing your arm out to the side (abduct the arm) you will feel the tip of the blade rotate outwards over the chest wall. This motion between the scapula and thoracic rib cage (scapulothoracic motion) is an important part of shoulder movement and must be recovered if you are to regain full range of motion after an injury. The upper end of the humerus is covered with thick muscle so it is difficult to feel. If you feel the acromion process and move your finger forwards to the front end of the bone then rotate your arm, you will feel the rotation of the head of the humerus through the muscle. The glenohumeral joint is too deep to feel.

The tip of the scapula can be felt if you put your other hand behind your back and reach up towards the shoulder. Normally you can just touch the lower tip of the opposite shoulder blade. If you now swing your arm out to the side (abduct the arm) you will feel the tip of the blade rotate outwards over the chest wall. This motion between the scapula and thoracic rib cage (scapulothoracic motion) is an important part of shoulder movement and must be recovered if you are to regain full range of motion after an injury. The upper end of the humerus is covered with thick muscle so it is difficult to feel. If you feel the acromion process and move your finger forwards to the front end of the bone then rotate your arm, you will feel the rotation of the head of the humerus through the muscle. The glenohumeral joint is too deep to feel.

Fracture of the tip of the scapula is usually an avulsion fracture. Powerful muscles attach to the lower tip of the scapula. These muscles act to either rotate or stabilize the scapula against the chest. Since most of the muscles that move the arm attach to the scapula, one important function of the muscles that go between the rib cage and the scapula is to hold the blade still. They tend to "lock" and clamp the scapula to the chest wall. In this situation, if a force on the arm is enough to move the scapula back away from the chest wall, the muscle attachment to the tip is pulled off. Bracing your arm before an impact may result in this injury. Usually it can be treated non-operatively.

Fracture of the tip of the scapula is usually an avulsion fracture. Powerful muscles attach to the lower tip of the scapula. These muscles act to either rotate or stabilize the scapula against the chest. Since most of the muscles that move the arm attach to the scapula, one important function of the muscles that go between the rib cage and the scapula is to hold the blade still. They tend to "lock" and clamp the scapula to the chest wall. In this situation, if a force on the arm is enough to move the scapula back away from the chest wall, the muscle attachment to the tip is pulled off. Bracing your arm before an impact may result in this injury. Usually it can be treated non-operatively.

Fractures of the glenoid occur due to the same type of force that fractures the neck of the glenoid. More commonly, a glenoid fracture occurs when the shoulder dislocates and a fragment of the joint goes with it. A fracture involving the glenoid results in an irregular portion of the joint surface. Unless the joint surface is perfectly aligned after the dislocation is back in joint, the fragments are usually treated by surgery (ORIF). Some surgeons may elect to manage this fracture with arthroscopic surgery.

Fractures of the glenoid occur due to the same type of force that fractures the neck of the glenoid. More commonly, a glenoid fracture occurs when the shoulder dislocates and a fragment of the joint goes with it. A fracture involving the glenoid results in an irregular portion of the joint surface. Unless the joint surface is perfectly aligned after the dislocation is back in joint, the fragments are usually treated by surgery (ORIF). Some surgeons may elect to manage this fracture with arthroscopic surgery. Glenohumeral dislocations result from the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) being moved beyond its limits. The most common position causing this dislocation is excessive abduction and external rotation. Simply put, when the level of the elbow is at or above the shoulder level the hand is forced backwards and the shoulder is therefore pushed forward, out of joint, by a "crank-shaft" action. Dislocation backwards also occurs. The humeral head may be fractured or dented from the impact of it hitting the glenoid rim on dislocation. This is very common after an anterior dislocation. This dent is called a Hill Sachs Lesion. Fortunately it is usually small and rarely needs treatment.

Glenohumeral dislocations result from the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint) being moved beyond its limits. The most common position causing this dislocation is excessive abduction and external rotation. Simply put, when the level of the elbow is at or above the shoulder level the hand is forced backwards and the shoulder is therefore pushed forward, out of joint, by a "crank-shaft" action. Dislocation backwards also occurs. The humeral head may be fractured or dented from the impact of it hitting the glenoid rim on dislocation. This is very common after an anterior dislocation. This dent is called a Hill Sachs Lesion. Fortunately it is usually small and rarely needs treatment.

With such a wide variety of injuries to the shoulder girdle it is not surprising that the treatment options are widely variable as well.

With such a wide variety of injuries to the shoulder girdle it is not surprising that the treatment options are widely variable as well.

Malunion means that the fracture heals in an incorrect position. This is frequently asymptomatic; the scapula often unites with fragments overlapping or rotated. However, because the scapula acts primarily as a site of attachment for muscles the new shape does not affect function and is rarely noticeable. The collarbone is just under the skin and any malunion can be felt as a swelling or overlap in the area. In rare cases small pieces of bone (spicules) from an angulated clavicle fracture may work their way through the skin and may need to be trimmed off.

Malunion means that the fracture heals in an incorrect position. This is frequently asymptomatic; the scapula often unites with fragments overlapping or rotated. However, because the scapula acts primarily as a site of attachment for muscles the new shape does not affect function and is rarely noticeable. The collarbone is just under the skin and any malunion can be felt as a swelling or overlap in the area. In rare cases small pieces of bone (spicules) from an angulated clavicle fracture may work their way through the skin and may need to be trimmed off.